“Let God lead my Heart, and my King lead my Sword.”

This is the banner that was prepared for the competition in 2019 – “On the Kings’ Road.”

Please, note that the banner presented is not a replica of the research findings due to material accessibility and tools unavailability. My goal was to make as close a reproduction as possible by using modern tools, materials, and techniques.

Also, one of my goals for this year is to remake this banner, improve the quality of embroidery and replace the cross with a different symbol, as I have no connection with Orthodox Christianity.

The following research represents the archeological findings, including examples of Fresca’s and different visual resources for Rus Early-Christian Culture and the period of War separation of the country (XII-XV century).

Чрьленъ стягъ, бѣла хорюговь, чрьлена чолка, сребрено стружіе — храброму Святьславличу! (“Blood Red Banner, white War Flag, attached to the silver spear for Brave Svyatoslavovich!” The Tale of Igor’s Campaign).

The banner was one of the essential accessories on the battlefield. It would show where the army should gather, inform about winning or losing the battle, helped to understand what families and cities are on the field.

The Banner presented today is a hand-embroidered device of the noble family which happens to be my device in SCA as well, the device of the Grand Prince, Ruricovich, and the Orthodoxtian Cross. The emblem of the king is on the fire-bird right wing, and the cross is on the left side. This represents the idea of following God and the King on the battlefield. “Let God lead my Heart, and my King lead my Sword.”

Let’s talk about some history.

History of Banners/Styags

The first publishers, in all cases, translated the banner as a “styag” (“styags”). As noted by M. Fasmer, the word “styag” dates back to ancient scandals. stö ng (ancient Swedish. – stang) – “pole” (Fasmer., 1987.) D. Dubensky, who etymologized the banner from “pulling together” and “pulling together,” remarked that in chronicles, the flag could mean like the chap. Military team banner, and regimental, as well as the army itself (Slovo. S. 52). Having “pounded” the flags, that is, attaching them to the poles, the troops in Ancient Russia lined up in battle order, which corresponds to the terms “putting banners” or “banners standing” (Yakovlev. Russian ancient banners). In miniatures of the Radzivilov annals in describing the events of the Popovic inventions. XII century, two types of banners are found: Rus. flags with a cross for “arsenal” and Polovtsian with a crescent, the latter being found only when describing the events of 1185 and the Don campaign of Vsevolod Yuryevich 1199, which is firmly connected with the famous place of the Word that Vsevolod can “Дон шеломы выльяти.”(Vsevolod can cross Don River)

In the 12th century, “styag” was increasingly understood as a banner and not a military unit. The word “flagman” is also found in the annals – the standard-bearer, just as the names “dragonarios” for the standard-bearer in Rome, “bandoforos” in Byzantium, and “banner” in Western Europe existed.

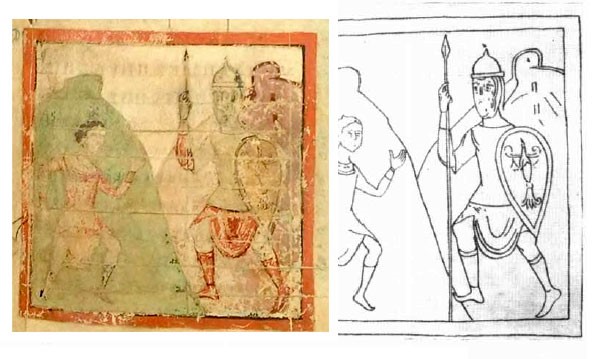

The extreme interest in the image of banners is the 14th-century frontlist – “The Chronicle of George Amartol.” It was compiled in the middle of the 9th century by the Byzantine monk George, who called himself Amartol (Sinner), then continued by another author until the middle of the 10th century and, probably, is illustrated at the same time. Many researchers believe that the translation from the Greek chronicles of Amartol was first done at the court of Yaroslav the Wise in the 40s of the XI century. In Russia, the text of this historical source has become unusually popular and has been repeatedly used in the Russian annals. Unique is the illustrated list of Amartol chronicles of the fourteenth century, from Tver, with miniatures where different warriors are presented with different banners. Monochrome red, green triangular elongated panels attached to the spear, and red rectangular narrow panels attached to the flagpole without a pommel, and lances with a spear-shaped top, to the pole of which a red or yellow close rectangular panel is connected, and multi-colored trunks-trunks depart from it.

In the 13th-century Galicia-Volyn chronicles, it is told about the accession of Prince Daniil Romanovich Galitsky in Galich after another exile: “Daniel entered his city, came to the church of the Most Holy Theotokos, and celebrated his father’s table, and celebrated the victory, and placed his banner at the German gate.” At the beginning of the 13th century, the Galicia-Volyn annals tell of the campaign of the princes Daniil and Vasilka Romanovich to the Polish city of Kalisz. Polish soldiers turned to their prince: “If the Russian flag is hoisted on the city walls, then to who do you honor?”. In these chronicle passages, we are talking about Polish and neighboring southwestern Russian lands, where there was a tradition of hanging banners and city banners on city walls, towers, and gates. This tradition also existed in the Principality of Galicia-Volyn, but in other regions of Russia, this custom was not.

Russian banners of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were cut with a “scarf.” The rectangular part of the cloth was called the middle; its length was greater than the height; a rectangular triangle (slope) was sewn to the panel with its short side. The material for the Russian banners was kamka (Kamchatka, Kamchatka pattern; “tin tuft,” that is, shiny) – Chinese silk fabric with patterns, or thin taffeta – smooth silk fabric. On the military banner, holy image devices and passages of texts from the Gospel were embroidered with silver, gold, and colored threads. Along the edge of the banner was decorated with a border or fringe.

As a rule, the royal army had several military banners, which were to be gathered under a sound signal. Sound signals were transmitted using pipes and tambourines. The annalistic story about the Battle of Lipitsky in 1216 says that Prince Yuri Vsevolodovich had “17 banners and 40 pipes, the same number of tambourines”, his brother Prince Yaroslav Vsevolodovich had “13 banners and 60 pipes and tambourines.”

If the enemy “reached the flag and the flag of the slander,” this meant defeat, and inevitably followed by an indiscriminate retreat or flight of the entire army. During the internecine battles, princely squads sought to capture the banner of the enemy. The most fierce battle was fought around the banner; all efforts were directed to capture the flag of the enemy since the fate of the military banner decided the outcome of the whole battle.

Symbols and devices

Most of the time, the banners had symbols of the Orthodox religion, saints, and phrases from the Bible. However, sometimes warriors duplicated the devices from their shields on their banners. So, I researched different shield pictures to understand what devices were used during that period.

First of all, it should be said that the finds of shields in Ancient Russia are very meager. There is a find in Pskov of a small almond-shaped shield, but it is not entirely clear whether it is a shield or some cutting board.

All that remains is to look through medieval miniatures, bas-reliefs, and medallions, which quite clearly capture the images of shields. And here, the difference from Western Europe clearly emerges, where heraldry bloomed violently. It supplied the European knights with the most picturesque emblems that passed to the shields of the knights and the warriors subordinate to them.

The most, it would seem, the main image on the shields of soldiers of the Christian faith. In Europe, where the Crusades and the Order of the Hospitallers, Templars, and Teutonic Knights set a certain rhythm of life, the cross was famous. On the other hand, it was not that popular in Rus. As mentioned above, it was mostly used on banners. A little more often, on the shields, there are predatory animals.

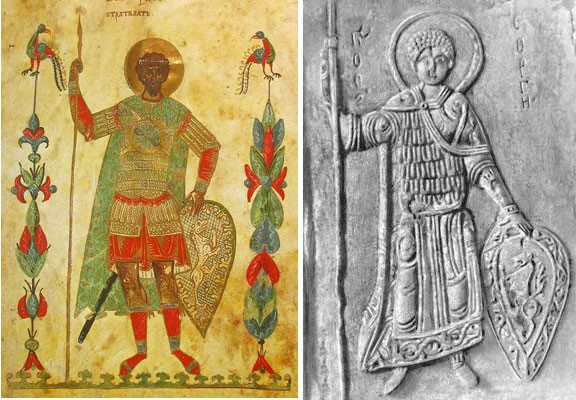

On the left is a miniature of the Fedorov Gospel, the border of the XIII-XIV centuries. On it is painted St. Fedor Stratilat. It was created in Yaroslavl, and it is still stored there.

On the right is another carving of the St. George Cathedral of St. George the Victorious. He, in fact, is depicted on it.

It is believed that the lion or leopard (often in symbolism, they are mixed into a single concept) is an ancient symbol of the Vladimir-Suzdal princes. It appeared around the XII century and is found not only in stone carvings but also on coins from the time of the Battle of Kulikovo and the Battle on the Ugra River.

Another shield with a representative of the fauna is on the Tver list of the chronicles of George Amartol (George Sinner). It contains information from the creation of the world to 842. This was the device I took as the base for my banner.

Embroidery, ornaments, and weaving pattern ornament usually serve not only esthetic purposes but also protecting, social status representation, and description of beliefs. I used the most common stitch for embroidery found during that period, and some of the patterns I used to replicate feathers and different fractures on the device. For more information on the Pictures used, please see the section on embroidery.

Central Device

As mentioned above, the device I chose is, luckily, my device in SCA and one of the devices I found during my research. Even though it is dated earlier than the XII century, the heraldry was passed from father to son over centuries, and it could still be used during the XII-XIII centuries,

Orthodox Christian Cross

There are some examples of crosses used on banners. The period I chose is the XIII century, and during that time, Orthodox Christianity was blooming in Rus. Moreover, it was an official religion. However, Russian culture is unique. It absorbed the elements from different cultures and religions and was able to mix them with pagan traditions. That is why crosses could be easily combined with animal protector symbols and ornaments.

Rarog

Raag (Ukrainian Rarig, Czech and Slovak. Rarog, Raroh, Raroch, Rarašek, Polish. Raróg) – in Slavic mythology, the fiery spirit associated with the cult of the hearth.

The symbol of the Falcon Rarog is on the coins of the Russian Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich and on the coins of the Russian Prince Yaroslav the Wise. The symbol of the Falcon Rarog was also found on the bricks of the Church of the Tithes, the first Christian Temple built by Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich, on the pendants and rings of the Russian princes and warriors, as well as on other items that were the property of the family of princes of Novgorod and Kyiv Rus. Some artifacts even show the eyes of the falcon Rarog.

Materials and Tools Used for Banner

- Gold untwisted thread

- Red Silk (100%), China

Embroidery Techniques

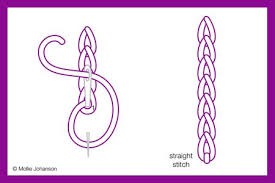

- “Stem” stitch.

The main stitch I used to fill in the wings and tail of the Rorag, the Bird body, and the Cross.

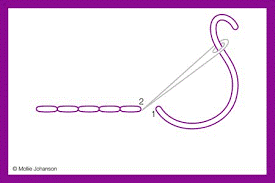

- “Run back” stitch.

This stitch was used for the edges of the banner.

- “Chain” stitch

This stitch was used for Bird’s tail and wings.

- Satin Stitch

This stitch was used for the tail and the head of the Rarog.

References

Anisimov, L. M, Slavic Mythology, n. d.

Arcihovsky, A. V. , Новгородские грамоты на бересте, 1945.

Chebotaev, N. (2015, January 21). Какие были рисунки на щитах русских дружин?. Retrieved from http://proshloe.com/kakie-risunki-na-shhitah-russkih-druzhin.html

Fasmer, M. Etymological Dictionary of the Russian Language. M., 1987. V. 3. P. 790

Fehner M.V. Kaluga. Borovsk., 1971

Khvoiko V.V., Древние обитатели Среднего Приднепровья и их культура в доисторические времена, 1913

Kolchin, B. A., Archeology, Ancient Rus; Living and Culture, 1997.

Saburova, M. A., Древняя Русь. Быт и культура. Москва, издательство «Наука», 1997.

Schapov, Y. N., Церковь в Древней Руси (До конца XIII в.) // Русское православие: вехи истории / Науч ред. А. И. Клибанов. — М.: Политиздат, 1989.

Prohorov, B.A, Великий Новгород. Энциклопедический словарь, 1881

Yakovlev, L. Rus ancient Banners, 1865

George Amartol, “The Chronicle of George Amartol”

Anonymous. Радзивиловская летопись. Retrieved from https://runivers.ru/doc/rusland/letopisi/?SECTION_ID=19639&PAGEN_1=20

[1] Blood Red Banner, white War Flag, attached to the silver spear for Brave Svyatoslavovich!

[2] Vsevolod can cross the Don River.